Despite being a former UK video nasty, The Cannibal Man (La semana del asesino, which literally translates as The Week of the Killer 1971) is one of the few that appeared on the infamous DPP list that are actually worth re-visiting. Directed by Eloy de la Iglesia, whose impact on Spanish cinema is equally often overlooked. He became notorious as a very outspoken socialist, gay filmmaker, whose movies broke the boundaries of the normally repressed cinema forced upon Spain under the oppressive dictatorship of Francisco Franco’s government. While his early films were unashamedly promoted in the exploitation market, de la Iglesia does not shy away from addressing controversial social issues, pushing the boundaries of the strict Spanish regime.

The Cannibal Man tells the story of Marcus (Vicente Parra) whose descent into insanity owes more to his social postion and cultural repression than any clichéd reasons of parental abuse or neglect. In fact, it is the state’s neglect which is largely at fault. Marcus, uneducated to the point of ignorance has to share his simple home with his truck-driving brother. This abode is in the middle of what is seemingly wasteland, where children and grown men alike hang around playing football and generally being a nuisance, and stray dogs prowl, looking for food. All around are the new, affluent residents of the high-rise apartments; the inhabitants often fleeing the city during the sweltering summer months. Most consider these residents above the rest of the populace; socially as well as literally. Néstor (Eusebio Poncela) looks out over the desolate landscape with his binoculars; a view which includes Marcus’ humble dwelling. Marcus works in a local slaughterhouse and it is here where the film opens, instantly filling the screen with graphic and disturbing images of cattle being hung and bled en masse while, clearly desensitised, Marcus casually stands eating a sandwich. The company, Flory, produces a range of top-selling soups and stews, not that this gives Marcus any pride. His girlfriend, Paula (Emma Cohen) is kept a secret, as her family would not approve of him, the fact she’s younger than him being one bone of contention. The disapproving looks the canoodling pair receive infers the age difference is noticeable. Grabbing a taxi on their way home, they start passionately kissing, much to the driver’s annoyance; “I don’t run a bordello”. The driver kicks them out, but Marcus refuses to pay the fare: “Shove your taxi!” He tries to push the driver, but receives a swift knee to the balls in response. However, when the driver hits Paula, Marcus picks up a rock and strikes him. Worried that Marcus may have killed him, he assures her, “You can only kill a person as easy as that in the movies”. Unconvinced, Paula goes home to worry some more. As he is walking back he bumps into Néstor, who is out walking his dog. They strike up a conversation, with Néstor asking why Marcus always looks so indifferent about him; he had hoped they would become good friends. Néstor speaks in a soft voice (certainly in the dubbed version), he’s obviously a sensitive, caring person as he shows his concern for Marcus.

The following day, Marcus reads that the taxi driver had died. Despite knowing that he acted in both self-defense and to protect Paula, he is clearly unsettled by the news. Paula is equally upset and convinced they will be found out. Back in his apartment, the couple makes love, set, metronome-style, to the sound of a ticking clock. Marcus’ sexual technique is astonishing – he provokes ecstatic responses from Paula while barely moving. Afterward, Paula insist they go to the police; “To tell them what? What happened in there?” he quips. Besides, they wouldn’t believe them anyway; he is, after all, just a menial worker – “The police will listen to the rich only”. His reluctance to face up to his actions leads Paula to question whether she should marry him after all. “I can’t believe anyone who won’t face reality. A marriage can’t be built on lies”; “So, I can go to the police or go to hell, is that it?” Paula assumes she’s convinced him and the couple kiss. Only for Marcus to strangle her while locking lips, the ticking clock stopping dead at the point Paula gasps her last breath.

Impassive, Marcus carries the body into his bedroom. The taxi driver’s death could be explained away as an accident, but this is a little harder to excuse. It’s clear that Marcus is becoming more and more depressed and detached from reality. The nature of his work has desensitised him to everything, including the carnage he is wreaking.

Steve, Marcus’ truck driving brother and roommate, returns home from work a day early, but Marcus doesn’t panic about what he’s done. With no beer in the fridge, the brothers go to Rosa’s, the local social club/bar. Steve can sense something is wrong. “It’s my girlfriend” he deadpans. Marcus confesses and Steve suggests going to the police. Flustered, Marcus unsuccessfully attempts to talk him into helping dispose of the body, so he takes a wrench and whacks at Steve’s head. Blood spatters across the room, dripping down the screen, obscuring the audience’s view. Placing Steve’s lifeless body side by side with Paula, Marcus sinks into his chair and the seriousness of his actions occurs to him for the first time.

Steve’s fiancée, Carmen (Lola Herrera) is waiting on the doorstep when Marcus arrives home from work, perturbed that he hasn’t been in touch when he was due home. She insists on waiting, but seems more keen on receiving her expected present: a wristwatch. So keen that she goes into his bedroom to look for it while Marcus has gone to get her a glass of water and some aspirin. It’s a fatal mistake, as she finds both Steve and Paula laid out on the bed. She will soon join them, as Marcus slits her throat in a moment that’s tense, gruesome and terrifying in equal measure. As Marcus is outside, getting some fresh air in the stifling heat, Néstor comes over for another chat. He had seen Carmen earlier and teases Marcus about her. He is clearly pushing buttons for a reaction, which Marcus is too polite to rise to. Going for a walk, Néstor’s demeanour flits between flirting and anxious, as he probes Marcus on his feelings. He takes an interest in his apartment, asking to see inside. “You wouldn’t like it; it’s full of memories, which wouldn’t interest you”. Néstor takes him off-guard; “You should bury them”. As a look of panic comes over Marcus’ face, he adds “Get rid of the memories”.

Marcus awakes on the sofa to the sound of Carmen’s father knocking aggressively on his door. Concerned that Steve is corrupting his daughter, he insists on knowing where they are. Marcus allows him into the room, where he joins the body count courtesy of a meat cleaver to the face. By now the room is beginning to smell, and flies are becoming a problem with the heat, so Marcus decides to chop the remains into smaller pieces and dispose of them in the best place he can think of: the meat processing plant. He uses perfume to mask the putrid smell in his holdall and apartment, which is attracting the strays as well as flies, but it isn’t enough to put off café waitress Rosa (Vicky Lagos), who invites herself around. Naturally, this doesn’t end well, and soon there is no one else in Marcus’ life to kill… except maybe his ever-so-friendly neighbour, Néstor. The climax takes place in Néstor’s ‘luxury’ high-rise apartment, where he shows Marcus the wonderful view – right into his home. It’s a tense, yet surprisingly tender scene in which the viewer (and Néstor himself) never quite knows whether Marcus will complete the killing spree, although it might actually be what Néstor wants.

In keeping with the rest of the film, the climax is very low-key. This is a movie more about social standing, loneliness and being an outsider as it is about a psycho killer. In fact, the more the film progresses, the more the viewer feels empathy for Marcus. He is a victim, who seals his fate the moment he strikes back at the aggressive taxi driver. Society has already judged him, so his actions have really no meaning but to delay the inevitable. Powerfully, de la Iglesia manages to portray Marcus’ mounting mental illness with realistic aplomb. Without the need of the ostentatious visuals of Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), it shows a man who, by the end of the film, is so distanced from reality that life has neither meaning nor emotion. On the opposite end of the scale, Néstor suffers similarly, trapped by (we assume) his sexuality, and lack of friends.

The sound of the clock aside, the soundtrack is relatively sparse. Some pulsating music throbs away in the background at times, and a bizarre triangle-like ‘ding’ accompanies the murders, as if a tally were being kept on a celestial abacus. Elsewhere, industrial sounds overpower some scenes, be it in the meat processing factory or overhead aircraft. These elements add to the oppressive feeling of the film; it manages to disturb without going over the top with horrific visuals. Although the film suffers from the usual synch-dubbing, the voice actors manage to convey the perfect emotions – or lack of them – to give the film a very natural feel. Marcus is more akin to the eponymous anti-hero in Henry – Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) than Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees.

The film’s original title makes much more sense than the Anglicised version. While there is the assumption that, due to Marcus disposing of the bodies in the meat processor, the public would be eating human flesh, there are no scenes of cannibalism. When given a bowl of Florey’s soup at the local bar, he instantly loses his appetite. Perhaps the cannibalism is a metaphor for the way the state eats up the squalid poor to feed the hungry rich? Either way, there is plenty of food for thought in de la Iglesia’s screenplay, which is co-written by Antonio Fos, whose other work includes The Vampires’ Night Orgy (1974) and the obscure drama El transexual (1977, which teamed Vicente Parra with Paul Naschy). Eusebio Poncela has had a long and varied career in Spanish cinema, recently appearing in the Lovecraft homage La herencia Valdemar (2010), with his character playing a larger role in its sequel La sombra prohibida. There’s even an early swipe at consumerism and food processing as we see a television advertisement for Florey’s soup, which claims to have “the flavour of good, rich meat”, although the eye-rolling child tucking into a bowl of atrocious looking broth does nothing to promote the idea.

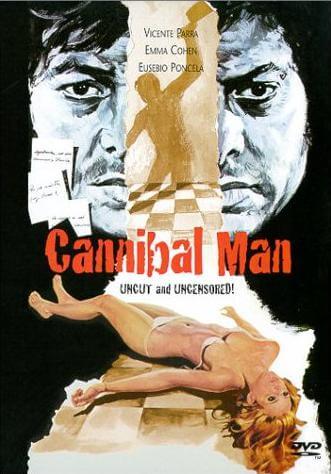

Once banned, it had a brief re-issue in the UK, albeit only on VHS (from Redemption, way back in 1993) and cut by 3 seconds (Carmen’s throat-cutting). While still shocking, it’s doubtful this would cause many problems if re-submitted today. The American DVD from Blue Underground is uncut, featuring an amazingly explicit cover: a gory close-up of the meat cleaver embedded in the face of Carmen’s father. Surprisingly, the film never received a contemporary American release, despite the fact one could imagine it playing in seedy cinemas during the 42nd Street heyday.

Severin has since released the film on Blu-ray in the US and it has turned up on Prime Video, although how long it will stay there is anyone’s guess.